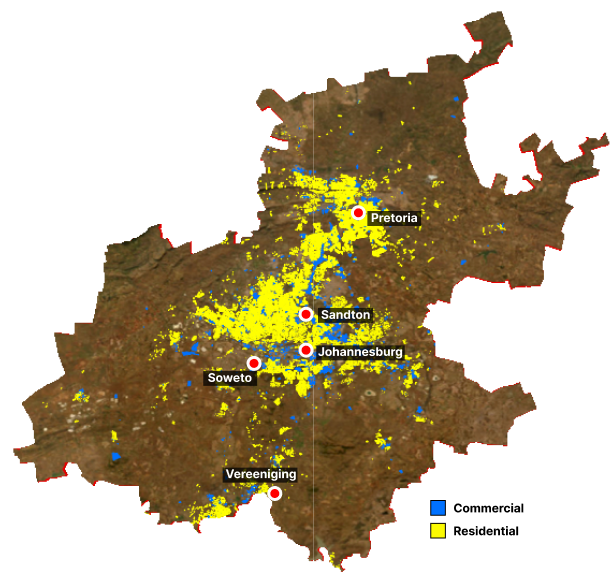

Gauteng

Leading an (unequal) rooftop solar boom

Gauteng, the engine room of South Africa’s economy, is undergoing an energy revolution – led by the middle class.

By the end of August 2024, about 1,800MW of renewable energy had been installed by homes and businesses across the land-constrained province, according to Eskom estimates. KwaZulu-Natal ranks a distant second, with a cumulative 811MW.

The boom in rooftop solar installations was a response to years of Eskom power cuts, known as loadshedding. has helped to relieve strain on the national electricity grid by reducing demand for Eskom-supplied power during the day.

However, there are concerns that as the private sector draws less from the grid, municipal finances will come under increasing pressure. This is because a large share of local government revenue is derived from buying electricity from Eskom and reselling it at a higher rate to households and businesses.

In 2023, the three big municipalities in Gauteng – the City of Joburg, Ekurhuleni and the City of Tshwane – got between 25% and 36% of their revenue from electricity sales.

So when homes and businesses switch to solar systems to escape loadshedding and cut their energy bills, municipalities could lose a critical source of income. As a result, poorer households – who cannot afford their own solar installations – may be left to foot the bill.

Municipalities use revenue from wealthier households and businesses to cross-subsidise services to the poor so if the revenue they receive from those customers decreases it threatens their ability to provide the poor with access to electricity.

These concerns are overblown, according to Gaylor Montmasson-Clair, a senior economist at Trade & Industrial Policy Strategies (TIPS) and facilitator of the South African Renewable Energy Masterplan.

In fact, municipalities could benefit from the rooftop solar trend by introducing feed-in tariff schemes, as the City of Cape Town has done.

By buying excess solar output from households and businesses and reselling it at their usual tariffs, municipalities could ensurethat the margins are higher than what they what they currently earn from distributing Eskom’s power.

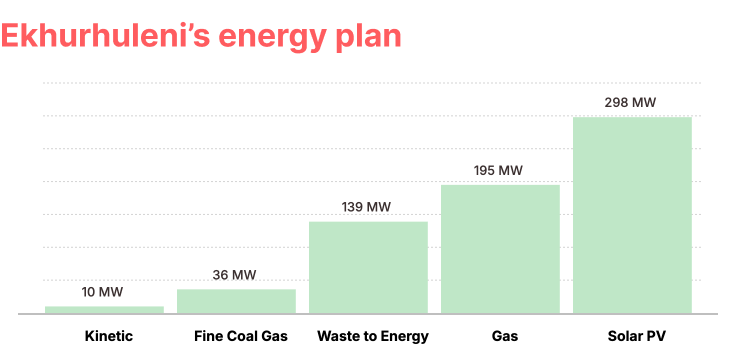

Cities and towns could also procure their own renewable energy and sell it on to homes and businesses, as Ekurhuleni plans to do. And municipalities could leverage the national free basic alternative energy programme to subsidise solar installations in low-income communities, thus ensuring those residents are also able to benefit directly from the shift to solar.

Regardless of the approach they take, Montmasson-Clair says municipalities will not be hurt by the private sector’s self-generation pursuits – at least any time soon.

Despite the recent surge, rooftop solar penetration levels remain low, and most homes and businesses with their own systems still draw power from the grid.

This means municipalities have plenty of time to rethink their funding models while they implement and benefit from feed-in tariff schemes.

Upmarket and off-the-grid

Upmarket and off-the-grid