Click on a power station icon to see the mines that supply coal to that power station. The mines are highlighted in green.

Mpumalanga

A province in flux

For decades, Mpumalanga has been the heartbeat of South Africa’s economy. The coal-rich province is dotted with mines and large-scale thermal power plants, which collectively employ tens of thousands of local residents.

However, a sense of unease is taking hold as Eskom’s older power stations near their end of life and the global shift to cleaner energy sources dampens the long-term outlook for coal exports.

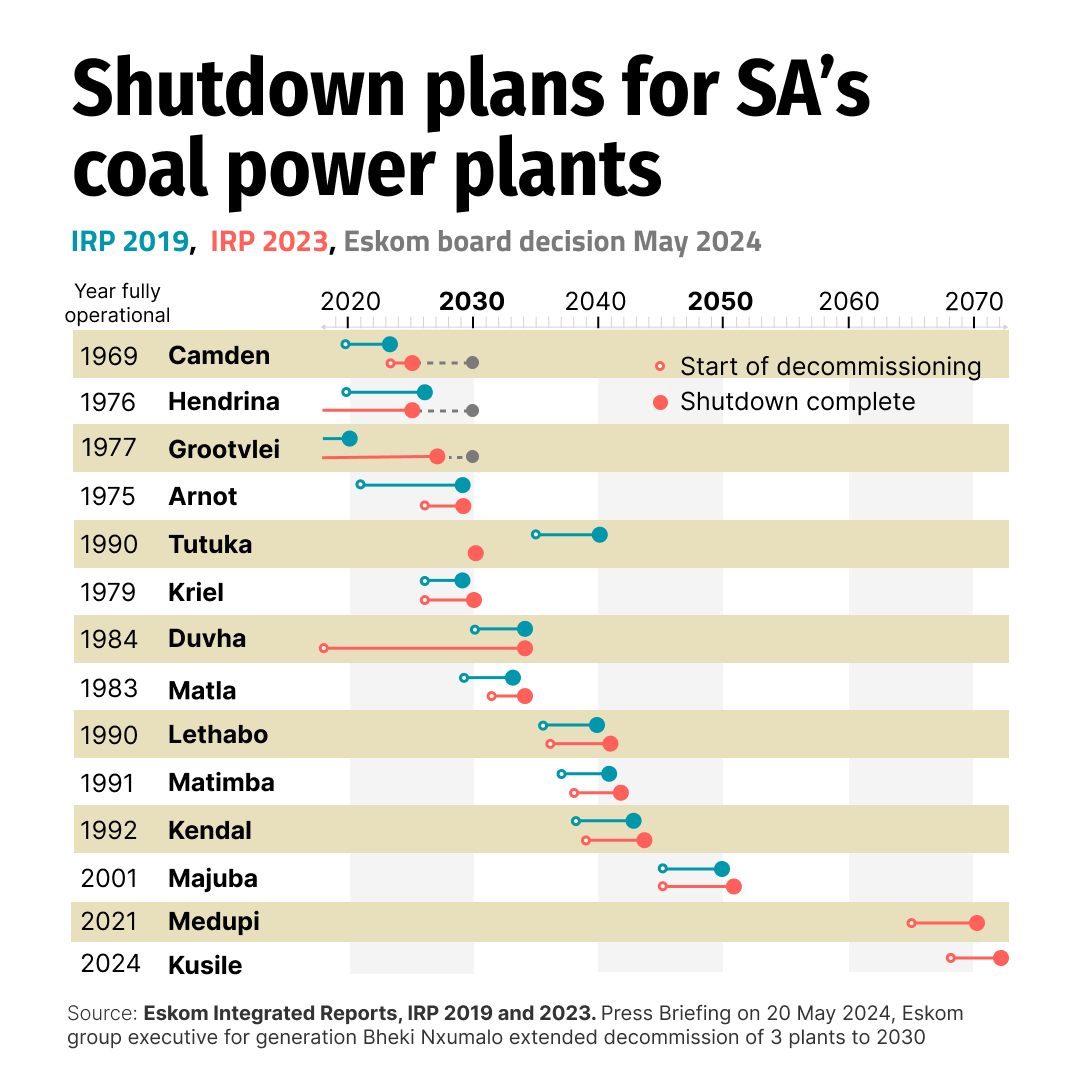

By 2030, seven coal-fired power plants in the province are scheduled to start or complete the decommissioning process after turning 50 years old, based on the 2019 version of the country’s energy plan, known as the Integrated Resource Plan (IRP). A new plan, released in 2023, adjusted the decommissioning plans by a year or two. In May 2024, Eskom's board approved a decision to delay the decommissioning to 2030 of three power stations that were scheduled to close a few years earlier.

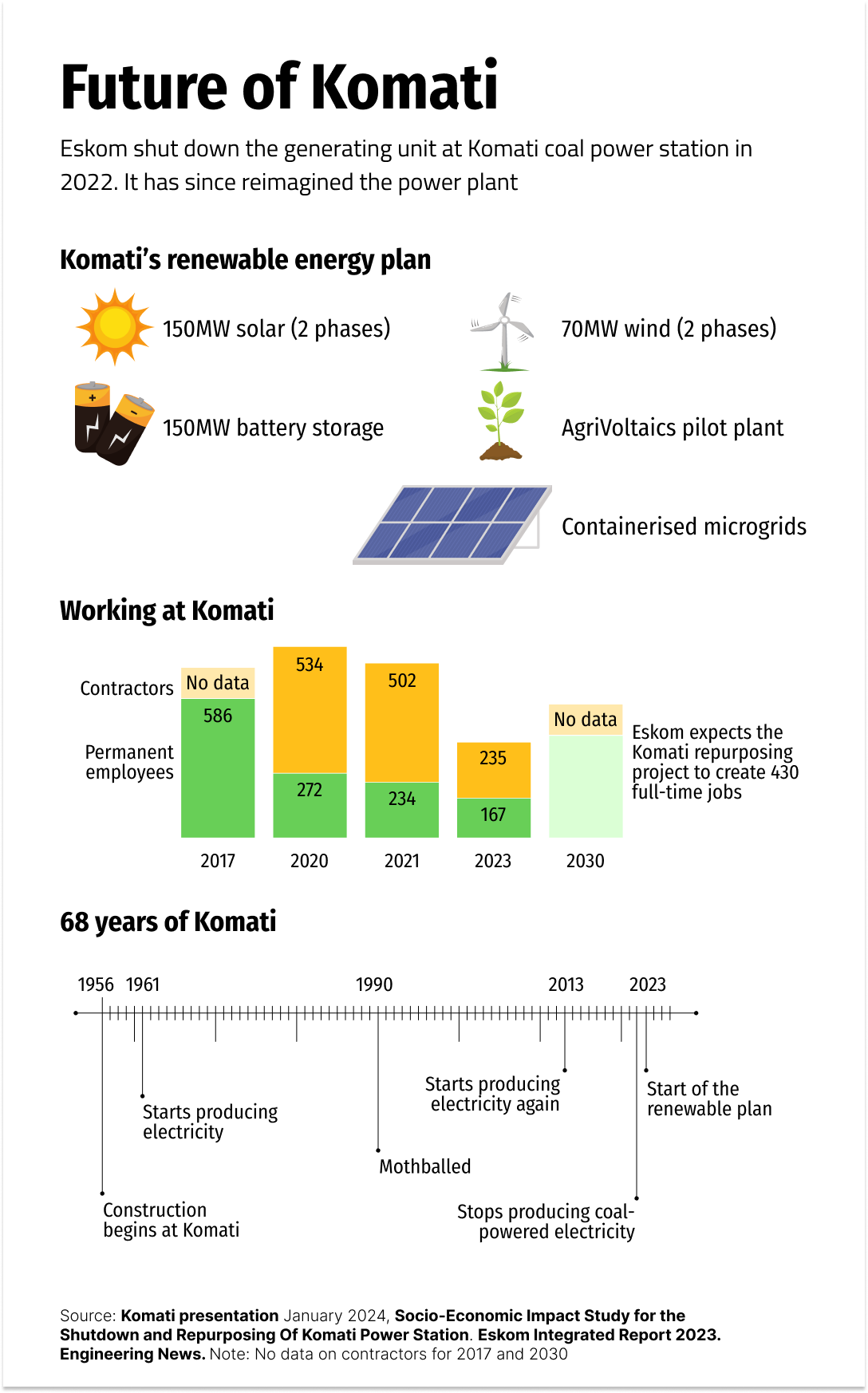

One facility – Komati – was retired from service in October 2022, more than six decades after it first started injecting power into the grid.

To avoid leaving the local community stranded, Eskom is converting the Komati site into a clean energy hub. In doing so, it aims to create a template for other ageing power plants in the vicinity to follow as they prepare for life after coal.

But although no Eskom workers lost their jobs at Komati, with many being redeployed to other stations, the project is so far doing little to allay fears that livelihoods will be lost in adjacent industries, and that towns in the coal belt will become derelict.

That’s partly because the repurposing project started too late, meaning the new job opportunities on site have mostly not yet materialised.

While Komati’s decommissioning process began as far back as 2017 when a decision was taken to no longer invest in its upkeep, those who were initially put in charge of the repurposing project dragged their feet for years, according to Eskom officials.

Misinformation has also stoked resentment, with senior government officials falsely claiming that the power station was shut because of the climate finance deal South Africa clinched at the COP26 climate conference in 2021.

Nevertheless, the bold vision for Komati – and by extension, the province – is starting to take shape.

For the time being, employees and community members are being retrained in preparation for the switch to renewables, which is planned to commence at scale in 2025.

The plan is to install, on site, up to 150MW of battery storage capacity, 70MW of wind turbines, three synchronous condensers to help strengthen the grid, and 150MW of agrivoltaics – where food is grown under raised solar panels. The size of the projects will ultimately be informed by environmental impact assessments.

Meanwhile, a microgrid manufacturing line was recently launched. The aim is to supply containerised solar-plus-storage units to far-flung communities in South Africa and other parts of Africa – a project that could become an important new revenue source for Eskom.

At the same time, accredited training facilities have opened their doors, giving local community members an opportunity to learn skills such as welding and installing rooftop solar systems.

The managers of nearby power stations that are nearing their end of life have been visiting Komati to learn from its wins and teething issues, according to those in charge of the flagship repurposing project.

Socioeconomic impact assessments have already been completed for plants that are next in line to be shut down, meaning they can get a head start on their transformations, according to Mandy Rambharos, former head of Eskom’s just energy transition strategy and now chief executive officer of Verra, which helps set global standards for climate action and sustainable development.

The tiny team that's steering the JET flagship

The tiny team that's steering the JET flagship